The dark side of plant-based food

5 min read

Nina Firsova/Shutterstock.com

Martin Cohen, University of Hertfordshire and Frédéric Leroy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

If you were to believe newspapers and dietary advice leaflets, you’d probably think that doctors and nutritionists are the people guiding us through the thicket of what to believe when it comes to food. But food trends are far more political – and economically motivated – than it seems.

From ancient Rome, where Cura Annonae – the provision of bread to the citizens – was the central measure of good government, to 18th-century Britain, where the economist Adam Smith identified a link between wages and the price of corn, food has been at the centre of the economy. Politicians have long had their eye on food policy as a way to shape society.

That’s why tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and grain were enforced in Britain between 1815 and 1846. These “corn laws” enhanced the profits and political power of the landowners, at the cost of raising food prices and hampering growth in other economic sectors.

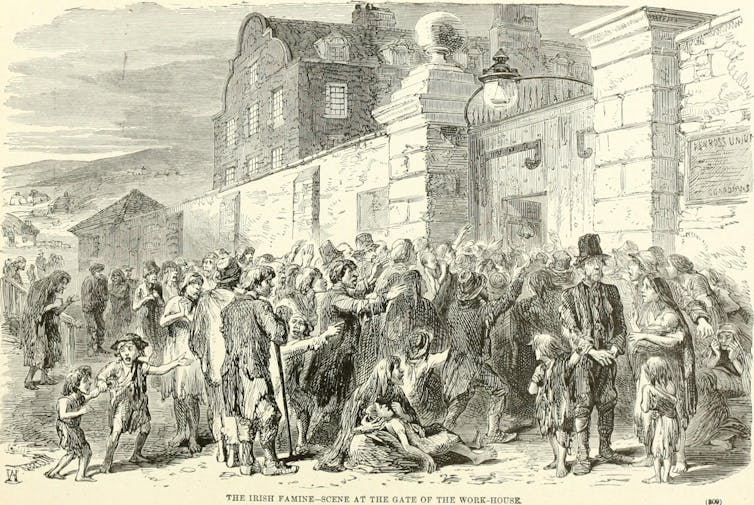

Over in Ireland, the ease of growing the recently imported potato plant led to most people living off a narrow and repetitive diet of homegrown potato with a dash of milk. When potato blight arrived, a million people starved to death, even as the country continued to produce large amounts of food – for export to England.

internetarchivebookimages/flickr

Such episodes well illustrate that food policy has often been a fight between the interests of the rich and the poor. No wonder Marx declared that food lay at the heart of all political structures and warned of an alliance of industry and capital intent on both controlling and distorting food production.

Vegan wars

Many of today’s food debates can also be usefully reinterpreted when seen as part of a wider economic picture. For example, recent years have seen the co-option of the vegetarian movement in a political programme that can have the effect of perversely disadvantaging small-scale, traditional farming in favour of large-scale industrial farming.

This is part of a wider trend away from small and mid-size producers towards industrial-scale farming and a global food market in which food is manufactured from cheap ingredients bought in a global bulk commodities market that is subject to fierce competition. Consider the launch of a whole new range of laboratory created “fake meats” (fake dairy, fake eggs) in the US and Europe, oft celebrated for aiding the rise of the vegan movement. Such trends entrench the shift of political power away from traditional farms and local markets towards biotech companies and multinationals.

Estimates for the global vegan food market now expect it to grow each year by nearly 10% and to reach around US$24.3 billion by 2026. Figures like this have encouraged the megaliths of the agricultural industry to step in, having realised that the “plant-based” lifestyle generates large profit margins, adding value to cheap raw materials (such as protein extracts, starches, and oils) through ultra-processing. Unilever is particularly active, offering nearly 700 vegan products in Europe.

Researchers at the US thinktank RethinkX predict that “we are on the cusp of the fastest, deepest, most consequential disruption” of agriculture in history. They say that by 2030, the entire US dairy and cattle industry will have collapsed, as “precision fermentation” – producing animal proteins more efficiently via microbes – “disrupts food production as we know it”.

Westerners might think that this is a price worth paying. But elsewhere it’s a different story. While there is much to be said for rebalancing western diets away from meat and towards fresh fruits and vegetables, in India and much of Africa, animal sourced foods are an indispensable part of maintaining health and obtaining food security, particularly for women and children and the 800 million poor that subsist on starchy foods.

To meet the 2050 challenges for quality protein and some of the most problematic micronutrients worldwide, animal source foods remain fundamental. But livestock also plays a critical role in reducing poverty, increasing gender equity, and improving livelihoods. Animal husbandry cannot be taken out of the equation in many parts of the world where plant agriculture involves manure, traction, and waste recycling – that is, if the land allows sustainable crop growth in the first place. Traditional livestock gets people through difficult seasons, prevents malnutrition in impoverished communities, and provides economic security.

Magdalena Paluchowska/Shutterstock.com

Follow the money

Often, those championing vegan diets in the west are unaware of such nuances. In April 2019, for example, Canadian conservation scientist, Brent Loken, addressed India’s Food Standards Authority on behalf of EAT-Lancet’s “Great Food Transformation” campaign, describing India as “a great example” because “a lot of the protein sources come from plants”. Yet such talk in India is far from uncontroversial.

The country ranks 102nd out of 117 qualifying countries on the Global Hunger Index, and only 10% of infants between 6–23 months are adequately fed. While the World Health Organization recommends animal source foods as sources of high-quality nutrients for infants, food policy there spearheads an aggressive new Hindu nationalism that has led to many of India’s minority communities being treated as outsiders. Even eggs in school meals have become politicised. Here, calls to consume less animal products are part of a deeply vexed political context.

Likewise, in Africa, food wars are seen in sharp relief as industrial scale farming by transnationals for crops and vegetables takes fertile land away from mixed family farms (including cattle and dairy), and exacerbates social inequality.

The result is that today, private interest and political prejudices often hide behind the grandest talk of “ethical” diets and planetary sustainability even as the consequences may be nutritional deficiencies, biodiversity-destroying monocultures and the erosion of food sovereignty.

For all the warm talk, global food policy is really an alliance of industry and capital intent on both controlling and distorting food production. We should recall Marx’s warnings against allowing the interests of corporations and private profit to decide what we should eat.![]()

Martin Cohen, Visiting Research Fellow in Philosophy, University of Hertfordshire and Frédéric Leroy, Professor of Food Science and Biotechnology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.