New Data Shows Where Americans Are Taking Advantage of Clean Energy Tax Credits

4 min read

Americans claimed more than $8 billion in climate-friendly tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act last year, according to new data released by the Treasury Department, a “significant” number that is higher than initially expected, officials said.

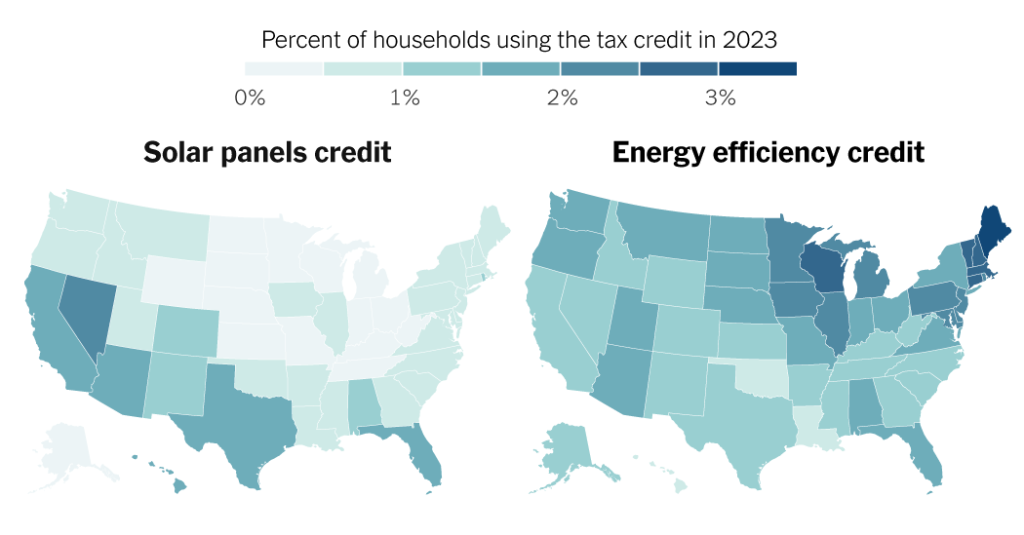

The bulk of the money, more than $6 billion, helped households install rooftop solar panels, small wind turbines and other renewable energy systems. These credits were most popular in sunny states, including much of the Southwest and Florida, the data shows.

Credits that helped Americans improve the energy efficiency of their homes by installing an electric heat pump or boiler, adding insulation, replacing windows and making other upgrades were most popular in the Northeast and Midwest.

A version of both tax credits has existed for years, but they were expanded and extended under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which invested at least $370 billion in clean energy programs across the U.S. economy. The tax incentives have proven so popular that the law’s final price tag is likely to be higher.

The new Treasury data offers the first detailed snapshot of how these more generous benefits were used in their first full year, by whom and where.

Wally Adeyemo, deputy secretary of the Treasury, told reporters on Tuesday that the tax credits have been “more popular than initially projected.”

More than 3.4 million households claimed at least one of the subsidies last year, adding up to more than $8 billion in total savings, according to the Treasury analysis. The nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation initially suggested the credits would cost $2.4 billion in their first year and around $4 billion in subsequent years.

The credit for solar panels was especially popular, the Treasury data shows, with more than 750,000 American households claiming it last year. A credit for heat pumps, meanwhile, was claimed on more than 260,000 tax returns. Some households may have claimed both.

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

Notes: Based on tax returns processed through May 23, 2024. The number of returns has been rounded to the nearest ten. Taxpayers may apply a credit toward more than one technology.

(Because the I.R.A. expanded an earlier, expired tax credit for energy-saving home improvements, some more efficient natural gas-burning appliances were also eligible for the subsidy.)

Former President Donald J. Trump has said that if he is elected in November and Republicans gain control of Congress, he would push to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act, particularly the tax credits for the purchase of electric vehicles, which were not included in the new Treasury analysis. But in a letter this week to House Speaker Mike Johnson, 18 House Republicans argued against repeal, saying it would harm investments made in the economy.

Mr. Adeyemo stressed that the upfront savings from the tax credits were only a part of the story, noting that households that install solar panels and switch to more efficient appliances would see lower utility bills for years to come.

Making the switch to cleaner energy also helps to guard against “spikes in fossil fuel energy prices, while improving the quality of the air we breathe and reducing carbon emissions,” Mr. Adeyemo said.

Treasury officials also highlighted that nearly half of the households that claimed at least one of the tax credits had incomes of less than $100,000. But about 75 percent of all tax filers had incomes under $100,000 in 2023, which meant that the credits still disproportionately benefited wealthier taxpayers.

James M. Sallee, an energy economist at the University of California, Berkeley, said that this distribution appears to be “substantially less regressive” than in previous years.

But he noted that tax credits tend to benefit wealthier people for a variety of reasons: They require consumers to pay up front and wait until tax season to recoup the cost and they sometimes require itemizing tax returns, a practice more common among more affluent households. The I.R.A.’s clean energy and efficiency credits also mostly apply to homeowners, who are usually wealthier than renters.

“The I.R.A. tried to break that trend by capping income on a number of provisions,” Dr. Sallee said. But, he added, “it’s hard to break away from when you operate through the tax code, which favors the rich.”

The Inflation Reduction Act did fund some rebates at the point of sale, which could help reduce upfront costs for more lower- and moderate-income homeowners looking to buy efficient appliances and make other improvements.

But those rebates have been slower to roll out than the federal tax credits because they require state and tribal governments to set up programs to manage them. So far, only New York and Wisconsin have started their rebate programs but another 19 states and the District of Columbia have applied for funding and expect to offer rebates by the end of the year.