The Agricultural Transition Plan should be a plan for nature positive farming – Inside track

5 min read

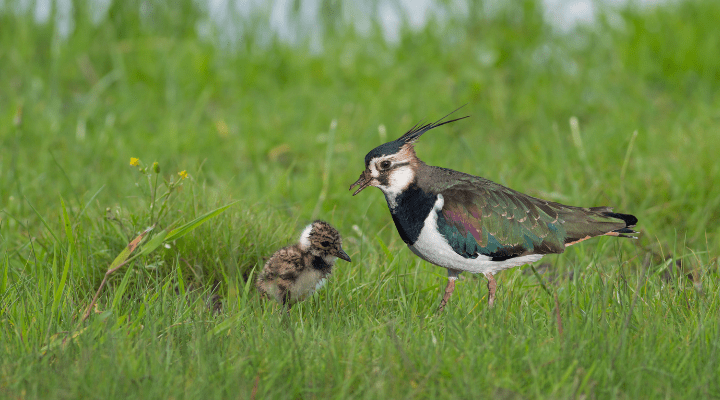

There are only seven years left to meet England’s species abundance target to halt nature decline by 2030 and then reverse it by 2042. Yet nearly one in six UK species are threatened with extinction and the farmland bird index has declined by 59 per cent since 1970. With 70 per cent of land in England farmed, the post-Brexit Environmental Land Management payment scheme must act as a crucial lever for recovering our iconic species and reviving the countryside. Government funded research demonstrates that at least 41 per cent of farmers must manage at least a tenth of their land for nature just to stabilise farmland bird populations, and 65 per cent to recover populations by 2042.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) will publish an updated Agricultural Transition Plan soon outlining the next steps in the transition from the EU Common Agricultural Policy to domestic ELM schemes. This will provide some detail on the ELM offer for 2024, including new and amended options and payment rates. What is less clear is whether it will finally provide a clear roadmap and comprehensive policy to back the transition to nature positive farming.

Nature positive farming is profitable and can boost the resilience of farm businesses in a changing climate, whilst safeguarding food security. But signals from Westminster are unclear, leading to confusion and frustration. Defra has prioritised an entry level ‘pick-n-mix’ approach to payments which just won’t add up to what’s needed, whilst the most ambitious elements of ELM are oversubscribed, with farmers who want to do more unable to participate.

If the government is serious about hitting critical targets and supporting farmers, action in five areas of agricultural policy is needed:

1. A clear plan and roadmap for environmental deliveryNature and climate targets won’t just fall into place; a credible, joined up and detailed delivery plan is necessary.

High uptake of schemes alone will not necessarily deliver. Defra must clearly set out how it will encourage and reward farmers to do the right actions in the right places. This means refining the 70 per cent scheme uptake target into something more meaningful. For example, what proportion of farmers should manage ten per cent of the land for nature? And what proportion of our watercourses should be buffered by trees, scrub, or flower rich margins?

A roadmap would provide a sense of direction, enable progress to be tracked and identify where the course needs correcting. This is essential to boost public and farmers’ confidence in ELM, creating a shared sense of how public monies will be used to deliver public goods.

2. Improve farmer access to the most rewarding and ambitious schemesCountryside Stewardship Higher Tier and Landscape Recovery offer the most impactful and tailored action within ELM. These schemes provide the best offer for farmers, including those who already do most to support nature on their farms. They overwhelmingly support small and upland farms, who require the most targeted support during the agricultural transition.

But both schemes are significantly oversubscribed, meaning farmers who want to do more for nature are being turned away. A decade ago, there were around 2,500 government funded higher tier equivalent agreements a year, compared with 300-500 now, which is a decrease of 80 per cent. This year, a fifth of farmers who applied to Countryside Stewardship Higher Tier were turned away.

In 2022, the first round of Landscape Recovery was also heavily oversubscribed, with only 21 of 50 applications taken forward. This problem could be solved by increasing investment in the schemes, and in Natural England which is crucial to them, and by setting an uptake target of 3,000 to 4,000 Countryside Stewardship Higher Tier agreements a year.

3. Set a clear path and ‘end-goal’ for the Sustainable Farming IncentiveTo meets its arbitrary 70 per cent uptake target, the government has prioritised the roll-out of the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) in a way that has put environmental delivery and value for money on hold.

The ad hoc design of the SFI, with a lack of meaningful involvement from environmental stakeholders, moves away from an approach based on directed choice and standards, returning to the traditional model of free choice for farmers over which actions they can choose to take (or ‘pick-n-mix’). Whilst the ability to pick any eligible SFI options in any combination creates flexibility, it can mean little is delivered for nature. This is like the failed Entry Level Stewardship (ELS) scheme which saw the same options adopted everywhere with little environmental benefit. It would be a missed opportunity to embed nature at the heart of farm businesses. Defra should use evidence-based measures, such as wildlife packages, to ensure environmental delivery and value for money.

4. Increase access to good quality advicePrevious schemes have shown advice to be a popular and effective way of putting nature at the heart of profitable and resilient farm businesses. Advice supports farmers to achieve the outcomes ELM pays for, reducing the rate of failure and preventing money and the farmer’s time being wasted. With more options now available and very little directed choice in the form of packages or standards (which group complementary options together to deliver for nature), advice is more important than ever. Defra should establish a Nature Positive Farm Advisory Service to maximise the benefit of ELM to farmers and the taxpayer.

5. Create a level playing field by re-establishing the regulatory baselineFrom January next year, cross compliance regulations (which have required farmers to meet certain conditions around farm management and good agricultural and environmental practice to qualify for funds under the Basic Payment Scheme) will cease to apply in the UK, leaving significant gaps in the protection of hedgerows, soils and water. Separating cross-compliance and Basic Payments is an important step in the transition to ELM, but failing to replace these standards jeopardises the shift to environmentally sustainable agriculture. Establishing a firm but fair regulatory baseline would, therefore, protect farmers and the environment. This could be done rapidly by copying long established cross compliance measures into domestic law where gaps exist.

Defra should use the agricultural transition to support the shift to more nature positive farming. Farmers need a clear pathway to follow, not repeated and confusing changes to policy. With a target-linked plan, more access to the higher tiers, good advice and a level playing field, Defra would have a recipe for success.

This post is by Verity Winn, senior policy officer (agriculture) at the RSPB.