Cloudy with a chance of meatballs

10 min read

John Clauser’s theory of climate explained.

Some of you will have heard of John Clauser because he was an awardee of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics for his role in the experimental verification of quantum entanglement. Some of you will have heard of him because the first thing that he did after winning the Nobel was join a climate denial organization and make some rather odd claims about climate science. And some of you will never have heard of him (in which case, feel free to skip this post!).

At no point in his long and, by all accounts, successful, career has he ever published a paper on climate[1]. He has not penned an article, nor even a blog post or a tweet on the topic, and so any scientific basis for his opinions (if any) has been opaque… until recently. In the last few months he has given two interviews in which he goes into to detail about what he describes as a ‘missing element’ in climate science and what he imagines the consequences are for climate change. The first interview was for the Epoch Times (a far right-wing newspaper and media organization affiliated with Falun Gong). The second was a podcast with the somewhat troubled Chris Smith, an Australian journalist. (The material is somewhat similar in each). And more comprehensively, it was repeated in a recent video lecture as well.

And what is this supposed ‘missing element’? Clouds.

Before we get into the details of what is going here, let’s look at some of the stranger claims about climate science he has made:

- The “IPCC and others” use a “cloud-free” Earth. [Odd claim, but simply not true].

- “fluctuation[s] in the cloud cover of the earth that causes a sunlight reflectivity thermostat that controls the climate, control the temperature of the earth, and stabilize it very powerfully and very dramatically, a mechanism heretofore totally unnoticed.” [Clouds as a damping mechanism on climate change have been discussed in detail since the 1960s at least].

- “The power in this thermostat in terms of what you can refer to as radiative forcing, this is how many watts per square meter of surface area are involved, and it is 200 times more powerful than the effect of CO₂, and methane.” [This is at least a quantitative claim, see below for it’s lack of veracity].

- “Interviewer: Are you suggesting that in none of these models the cloud cover is actually included? Dr. Clauser: Indeed” [Again, just not true].

- “They really didn’t mention anything like this in the early IPCC reports.” [Simply false e.g. IPCC First Assessment Report (Chapter 3) from 1990].

- “The two most recent IPCC reports did not discuss clouds” [Totally untrue].

- “It’s [the albedo is] kept the same” [False – for instance here is a paper (Loeb et al, 2020) comparing the changes in albedo in models to the CERES observations].

- “I haven’t talked to any of the modelers” [This is obvious!]

- “The 40 models of the IPCC – most of which came from the Goddard Institute of Space Studies” [Where does this come from?]

Blame Al Gore? or Steve Koonin? the National Academies? or Art Robinson?

Apparently Clauser realized the problem with clouds because Al Gore only discussed a cloud-free Earth in his movie. That isn’t true of course – there are plenty of clouds in the Apollo 17 photo he uses to illustrate the impact of seeing Earth from space and it’s in his description of the Earth’s Energy balance. Possibly the confusion comes from him also highlighting an image from Tom Van Sant (left) that he explicitly states is a mosaic of cloud-free images, but at no point does he indicate that clouds aren’t important! Additionally, Clauser credits Steve Koonin’s book with the notion that no climate models have skillfully hindcast the past century (not true, but I’m not sure what the book does claim – Koonin does not appear to have made such a claim in his presentations AFAICT – let me know in the comments if this needs amending). And finally, he claims that the ‘original’ 2003 National Academies report (a bit unclear what this means) made a ‘whole series of mistaken statements’ about clouds. The only relevant 2003 NRC publication is the “Understanding Climate Feedbacks” report, which is possibly what Clauser is referring to[2], but that mostly makes very sensible recommendations about research priorities in cloud feedbacks and isn’t obviously mistaken in any of its claims. But it turns out that Art Robinson (of the Oregon Petition fame) was his college roommate many decades ago, and so perhaps we don’t need to look much deeper into where he gets his (mis)information.

Clauser-ology translated to recognizable climate science

That clouds affect the climate has been known since antiquity, and their response to climate change has been discussed, analyzed, and modeled in detail at least since the 1970s. Notably, of the two models assessed in the 1979 Charney report, one (from GFDL and Manabe, who was awarded the Nobel in Physics the year before Clauser) had fixed (not zero) clouds, but the second (from GISS and Hansen) had variable clouds. The differences in their cloud feedback (zero in the first case and positive in the second) were the main reason why their climate sensitivity differed (2ºC and 4ºC respectively). It is still the case that variations in cloud feedbacks are the dominant source of variability of climate sensitivity in models (Zelinka et al, 2020).

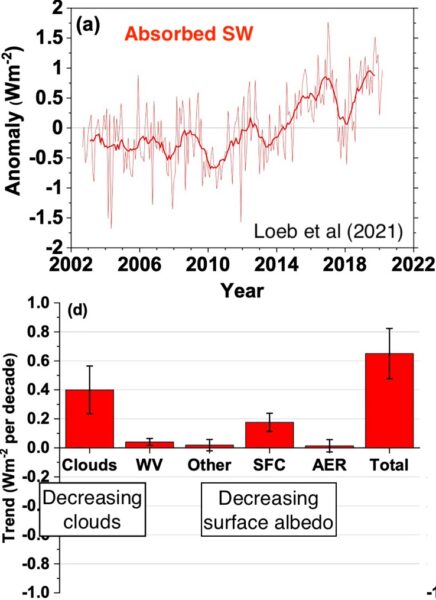

Clauser’s claim that clouds don’t change in models (no cloud feedback) is only correct for that original 1979-vintage GFDL model, but wasn’t true for other models then or now, or even the 1980s-era GFDL models. Clauser’s other claim, that clouds will change to counter any radiative imbalance, is a statement that clouds are a negative feedback (and indeed a very strong negative feedback). Equivalently, this is a statement that climate sensitivity to increasing forcings (such as CO2) is negligible. But if this were true, it would be impossible to sustain a net energy imbalance for the climate (more energy coming in than leaving). Clouds would change to match any change in the radiative forcing without needing much of a change in surface temperatures. However, not only is there an obvious energy imbalance (as seen by the growth of ocean heat content), it’s actually accelerating Loeb et al., 2022. These observations are incompatible with strong negative short wave cloud feedback – indeed, as the planet has warmed, albedo has gone down – the opposite of what Clauser’s theory would predict. To be fair, the detailed attribution for the trends in SW and LW radiative fluxes over the last twenty years are still somewhat in flux (Schmidt et al, 2023), but not by that much! Also missing is any realization that clouds also contribute to the greenhouse effect (roughly 25% of the total) and so whether cloud changes warm or cool depends very much on where the clouds are (high clouds have a very different effect than low clouds for instance).

Running the Numbers

A lot of Clauser’s confusion can be seen when he starts to get quantitative. He makes a number of specific claims: that the cloud feedbacks are 100 times stronger than the forcing from CO2, but this is wrong in a very fundamental way (feedbacks and forcings don’t even have the same units), and also in how he calculates it (see below). He also confuses radiative forcing (the impact of an instantaneous change in a component) with the energy imbalance at any point (which is affected by the feedbacks and temperature changes). He, however, goes seriously off the rails when he estimates the impact of clouds on the radiation budget. We can measure directly how much solar radiation arrives at the Earth and once you spread it over the surface of the Earth, there is about 340 W/m2. Additionally, we can measure how much of that radiation is reflected (from ice, ground surface, and clouds etc.). It’s about 100 W/m2, implying the average planetary albedo (reflectivity) is about 29%. Clauser however takes that number, removes 80 and 20 W/m2 for atmospheric absorption by ozone (!!) and backscatter to get 240 W/m2, and then assumes that with the average cloud coverage (67%)[3] and a typical albedo for a thick cloud (90%), that the clouds will reflect 145 W/m2. This is totally wrong (since we know that this is much larger than the actual measured total reflected short wave – only 100 W/m2). He is neglecting the fact that half the clouds are on the nighttime side of the Earth (and not reflecting anything), and that [Update 11/19: this is already factored in, thanks to JNG for noticing] cloud albedo depends on cloud thickness (so not all of the 67% will be have such a high albedo). Once you factor those things in, you end up with the standard numbers which is roughly half of what Clauser claims.

With respect to the cloud feedback, Clauser uses two end members to estimate the size of the effect. However, feedbacks are measured in (W/m2) per ºC – i.e. how much do they perturb the radiation balance as a function of the change in surface temperature. For instance, the (dominant, negative) Planck feedback is about -0.3 W/m2/ºC (i.e. the upward flux of LW from the surface increases by 0.3 W/m2 for every degree change in surface temperature). A strong negative cloud feedback would have a similar value, though IPCC estimates it to be positive (amplifying) 0.42 [–0.10 to +0.94] W/m2/ºC.

Clauser’s calculation takes two massive perturbations in clouds (from 50% to 75%), estimates the net forcing (incorrectly) as ~54 W/m2, and neglects the change in temperatures that should have generated such large shifts. But we know that total SW cloud radiative forcing is about -45 W/m2, thus a change in cloud cover of 25% (huge!) would imply a perturbation of only(!) ~17 W/m2 (and smaller still if you include the LW effects). However, these changes in cloud cover are absurd and would be way outside the linear regime that feedback theory is based on. Realistic variations in cloud cover are more likely on the order of a few % (interannually, smaller still on climate scales), and so SW effects could conceivably be a couple of W/m2, and with total feedbacks half that, at most (though the devil is in the details). Thus in comparison with the anthropogenic radiative forcing which is now over 2.5 W/m2, it is certainly not ‘100 times’ larger. And we still have to factor in the changes in temperature.

Over the last 20 years or so, temperatures have increased about 0.5ºC, and we have measurements of the global albedo (and SW changes) from CERES. If Clauser was correct, that warming should have been counteracted by an increase in cloud cover and reflected shortwave. Unfortunately, this is the opposite of what has happened – cloud cover, albedo and reflected shortwave have all decreased over that time (Fig 2a in Loeb et al, 2021).

Clouding the picture

So where does this leave us? Effectively, we have an overconfident Nobel Prize winner, who hasn’t done their homework in an area outside their field, who makes very obvious errors, and whose fame is being capitalized on by the forces of denial. Not really an original story (c.f. Kary Mullis, Linus Pauling, etc.), but still a bit of a shame.

[1] His PhD supervisor while at Columbia (1964-1969) was Pat Thaddeus who was a scientist at GISS until 1986, and it’s conceivable that he met Jim Hansen there since they overlapped for a couple of years. But this was before there was much Earth Science research at GISS.

[2] I’ve no idea why he claims this is the ‘original’ report. The 1979 Charney report has a much greater claim to that title.

[3] Cloud fraction is actually a very tricky concept and so this number is very dependent on the methodology – for instance how optically thick does a cloud need to be to count? Some folks have argued that cloud coverage is actually 100% if you include the super thin clouds. Of course, the albedo of the cloud depends on its thickness too.

References

N.G. Loeb, H. Wang, R.P. Allan, T. Andrews, K. Armour, J.N.S. Cole, J. Dufresne, P. Forster, A. Gettelman, H. Guo, T. Mauritsen, Y. Ming, D. Paynter, C. Proistosescu, M.F. Stuecker, U. Willén, and K. Wyser, “New Generation of Climate Models Track Recent Unprecedented Changes in Earth’s Radiation Budget Observed by CERES”, Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 47, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086705

M.D. Zelinka, T.A. Myers, D.T. McCoy, S. Po‐Chedley, P.M. Caldwell, P. Ceppi, S.A. Klein, and K.E. Taylor, “Causes of Higher Climate Sensitivity in CMIP6 Models”, Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 47, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085782

N.G. Loeb, M. Mayer, S. Kato, J.T. Fasullo, H. Zuo, R. Senan, J.M. Lyman, G.C. Johnson, and M. Balmaseda, “Evaluating Twenty‐Year Trends in Earth’s Energy Flows From Observations and Reanalyses”, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, vol. 127, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2022JD036686

G.A. Schmidt, T. Andrews, S.E. Bauer, P.J. Durack, N.G. Loeb, V. Ramaswamy, N.P. Arnold, M.G. Bosilovich, J. Cole, L.W. Horowitz, G.C. Johnson, J.M. Lyman, B. Medeiros, T. Michibata, D. Olonscheck, D. Paynter, S.P. Raghuraman, M. Schulz, D. Takasuka, V. Tallapragada, P.C. Taylor, and T. Ziehn, “CERESMIP: a climate modeling protocol to investigate recent trends in the Earth’s Energy Imbalance”, Frontiers in Climate, vol. 5, 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2023.1202161