What Is Wind Energy? Definition and How It Works

8 min read

Wind energy is electricity from the naturally flowing air in the Earth’s atmosphere. As a renewable resource that won’t get depleted through use, its impact on the environment and climate crisis is significantly smaller than burning fossil fuels.

We can create wind energy by erecting something as simple as a set of 8-foot sails positioned to capture prevailing winds that turn a stone and grind grain (a gristmill). Or, a wind energy structure can be as complex as a 150-foot vane turning a generator that produces electricity to be stored in a battery or deployed over a power distribution system. There are even bladeless wind turbines.

As of 2021, more than 67,000 wind turbines operate in the United States, in 44 states, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Wind energy mechanisms generated about 8.4% of the electricity in the U.S. in 2020. Worldwide, wind provides about 6% of the world’s electricity needs. Wind energy is growing year-over-year by about 10% and is a key part of most climate change reduction and sustainable growth plans in several countries, including China, India, Germany, and the United States.

Wind Energy Definition

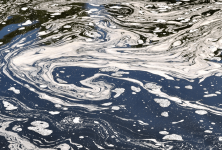

Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

Humans use wind energy in many ways, from the simple (it’s still used to pump water for livestock in more remote locations) to the increasingly complex—think of the thousands of turbines that dominate the hills cutting through Highway 580 in California (pictured above).

The basic components of any wind energy system are fairly similar. There are blades of some size and shape connected to a drive shaft, and a pump or generator that uses or collects the wind energy. If the wind energy is used directly as a mechanical force, like milling grain or pumping water, it’s called a windmill; if it converts wind energy to electricity, it’s known as a wind turbine. A turbine system requires additional components, such as a battery for electricity storage, or is connected to a power distribution system like power lines.

Nobody knows when a human first harnessed the wind, but wind energy moved boats on Egypt’s Nile River around 5,000 B.C. By 200 B.C., people in China used wind to power simple water pumps and inhabitants of the Middle East used windmills with hand-woven blades to grind grain. Over time, wind pumps and mills helped produce many kinds of food there, and the concept spread to Europe, where the Dutch built large wind pumps to drain wetlands—from there the idea traveled to the Americas.

Wind Energy Basics

Wind occurs naturally when the sun heats the atmosphere, through variations in the Earth’s surface, and from the planet’s rotation. Wind can then increase or decrease due to the influence of bodies of water, forests, meadows and other vegetation, and elevation changes. Wind patterns and speeds vary significantly across terrain and seasonally, but some of those patterns are predictable enough to plan around.

Site Selection

The tops of rounded hills, open plains (or open water for offshore wind), and mountain passes (where wind is naturally funneled, producing regular high wind speeds) are the best locations to place a wind turbine. Generally, the higher the elevation the better, since higher elevations usually have more wind.

Wind energy forecasting is an important tool for siting a wind turbine. Several wind speed maps and data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) or the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in the U.S. provide these details.

One should conduct a site-specific survey to assess local wind conditions and determine the best direction to place wind turbines for maximum efficiency. Anyone intending to build a wind turbine should track wind speed, turbulence, direction, air temperatures, and humidity in the desired location, for at least a year. After evaluating that information, it’s easier to construct turbines that will deliver predictable results.

Wind isn’t the only factor for siting turbines. Developers for a wind farm must consider how close the farm is to transmission lines (and cities that can utilize the power); possible interference to local airports and plane traffic; underlying rock and faults; flight patterns of birds and bats; and local community impact (noise and other possible effects).

Most larger wind projects are designed to last at least 20 years, if not more, so these factors must be considered over the long term.

Types of Wind Energy

Utility Scale Wind Energy

These are large-scale wind projects designed to be used as a source of energy for a utility company. They are similar in scope to a coal-fired or natural gas power plant, which they sometimes replace or supplement. Turbines exceed 100 kilowatts of power in size and are usually installed in groups to provide significant power—currently, these types of systems provide about 8.4% of all energy in the United States.

Offshore Wind Energy

These are generally utility-scale wind energy projects that are planned in the waters off coastal areas. They can generate tremendous power near larger cities (which tend to cluster closer to shore in much of the United States). Wind blows more consistently and strongly in offshore areas than on land, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Based on the organization’s data and calculations, the potential for offshore wind energy in the U.S. is more than 2,000 gigawatts of power, which is two times the generating capacity of all U.S. electric power plants. Worldwide, wind energy could provide more than 18 times what the world currently uses, according to the International Energy Agency.

Small Scale or Distributed Wind Energy

This type of wind energy is the opposite of the examples above. These are wind turbines that are smaller in physical size and are used to meet the energy demands of a specific site or local area. Sometimes, these turbines are connected to the larger energy distribution grid, and sometimes they are off-grid. You’ll see these smaller installations (5-kilowatt size) in residential settings, where they might provide some or most of a home’s needs, depending on weather, and medium-sized versions (20 kilowatts or so) at industrial or community sites, where they might be part of a renewable energy system that also includes solar power, geothermal, or other energy sources.

How Does Wind Energy Work?

The function of a wind turbine is to use blades of some shape (which can vary) to catch the wind’s kinetic energy. As the wind flows over the blades, it lifts them, just like it lifts a sail to push a boat. That push from the wind makes the blades turn, moving the drive shaft that they’re connected to. That shaft then turns a pump of some kind—whether directly moving a piece of stone over grain (windmill) or pushing that energy into a generator that creates electricity that can be used right away or stored in a battery.

The process for an electricity-generating system (wind turbine) includes the following steps:

Wind Pushes Blades

Ideally, a windmill or wind turbine is located in a place with regular and consistent winds. That air movement pushes specially designed blades that allow the wind to push them as easily as possible. Blades can be designed so they are pushed upwind or downwind of their location.

Kinetic Energy Is Transformed

Kinetic energy is the free energy that comes from the wind. For us to be able to use or store that energy, it needs to be changed into a usable form of power. Kinetic energy is transformed into mechanical energy when the wind meets the windmill blades and pushes them. The movement of the blades then turns a drive shaft.

Electricity Is Generated

In a wind turbine, a spinning drive shaft is connected to a gearbox that increases the speed of the rotation by a factor of 100—which in turn spins a generator. Therefore, the gears end up spinning much faster than the blades being pushed by the wind. Once these gears reach a fast enough speed, they can power a generator that produces electricity.

The gearbox is the most expensive and heavy part of the turbine, and engineers are working on direct drive generators that can operate at lower speeds (so they don’t need a gearbox).

Transformer Converts Electricity

The electricity produced by the generator is 60-cycle AC (alternating current) electricity. A transformer may be needed to convert that to another type of electricity, depending on local needs.

Electricity Is Used or Stored

Electricity produced by a wind turbine might be used on site (more likely to be true in small or medium-sized wind projects), it could be delivered to transmission lines for use right away, or it could be stored in a battery.

More efficient battery storage is key for advancements in wind energy in the future. Increased storage capacity means that on days when the wind blows less, stored electricity from windier days could supplement it. Wind variability would then become less of an obstacle to reliable electricity from wind.

What Is a Wind Farm?

A wind farm is a collection of wind turbines that form a type of power plant, producing electricity from wind. There’s no official number requirement for an installation to be considered a wind farm, so it could include a few or hundreds of wind turbines working in the same area, whether on land or offshore.

Wind Energy Pros and Cons

Pros:

- When properly placed, wind energy can produce low-cost and nonpolluting electricity about 90% of the time.

- There is minimal waste generated by a wind farm—nothing needs to be carted away and dumped, no water supply is needed to cool machinery, and there’s no effluent to scrub or clean.

- Once installed, wind turbines have a low operating cost, as wind is free.

- It’s space flexible: You can use a small turbine to power a home or farm building, a large turbine for industrial energy needs, or a field of giant turbines to create a power plant-level source of energy for a city.

Cons:

- Wind reliability can vary. In addition, weak or strong winds will shut down a turbine and electricity won’t be produced at all.

- Turbines can be noisy depending on where they are placed, and some people don’t like the way they look. Home wind turbines might offend neighbors.

- Wind turbines have been found to harm wildlife, especially birds and bats.

- They have a high initial cost, though they pay for themselves relatively quickly.