Science is not value free

4 min read

An interesting commentary addressing a rather odd prior commentary makes some very correct points.

Back a few months there was a poorly argued and rather confusing commenary by Ulf Büntgen (Buntgen, 2024) that started:

I am concerned by climate scientists becoming climate activists, because scholars should not have a priori interests in the outcome of their studies. Likewise, I am worried about activists who pretend to be scientists, as this can be a misleading form of instrumentalization.

In the piece, the targets of his concern were not really defined and the general point that ‘scientists should not have a priori interests in the outcome of their studies’ is simply untenable. It is one thing to state that scientists should beware confirmation biases (very sensible), but quite another to say that scientists must have no interest in the answer. Should a doctor working on a vaccine not want it to work? Should a conservation biologist not want the endangered species they are working with to survive? Should a climate scientist not want to keep the seas from rising? The notion that scientists don’t care about their results is bizarre.

This is of course an appeal to the ‘value-free ideal’ of science, which at one point was held up as a valid goal, but was soon recognised by philosophers to be a fallacy, though it still holds sway with some scientists and members of the general public. The comment by van Eck et al. makes this point very clearly and lays out a far more realistic guide to how climate science in particular can succeed when scientists are open about the values that guide them, and transparent about the reasons for their advocacy, or indeed, activism.

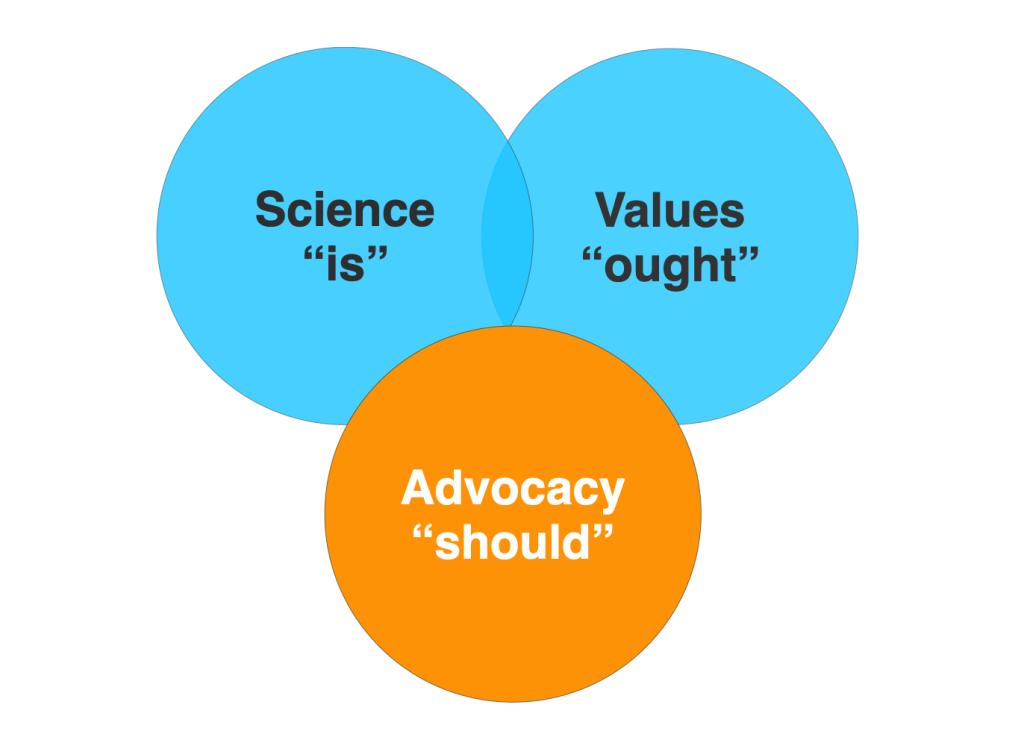

In my public talks about communication I often make the point that a scientist’s advocacy (suggesting specific actions) arises from a combination of their knowledge of the science (what is) and their values (what they consider important):

It is correct that a knowledge of “what is”, does not determine on its own what “should be” (something Hume recognised centuries ago), and so science per se does not determine policies. But advocating policies divorced from science is a recipe for inefficiency and failure.

A major problem with Büntgen’s argument (and other critiques of so-called ‘stealth advocacy’) is that since no scientist lives up to the value-free ideal, anything a scientist advocates can be dismissed by demonstrating that they do have values or preferences or, heaven forbid, a political stance. Indeed, we see this dynamic arising all the time – for instance, Patrick Brown declaring that any science that appears in Science or Nature (including his own apparently) is compromised because the editorial boards of these journals have expressed political opinions (and are explicit about their values).

There are two possible responses to this dynamic. Scientists can hide their values, and avoid expressing any opinions, or they can be transparent about them and explicit about how they motivate their advocacy. The former approach is fragile because scientists do have values and opinions, and their work will still be declared to be tainted if it’s politically uncomfortable. The latter approach is robust, because the scientist owns their advocacy and do not have to defend an indefensible ideal.

People are often enculturated to the idea that science (and by extension, scientists) are purely objective (think of Star Trek’s Mr. Spock), and that science rises above the messy business of being human. But while science as a process does manage to overcome many individual biases (through replication, repeated testing, and successful predictions), there are still strong imprints of the values of previous generations of scientists in what we study, how we study it, and who gets to study it.

When someone is confronted by a scientist’s advocacy that they disagree with, it can be tempting to criticise it, not for the values upon which it is based, but for the temerity of advocating anything at all. Such a critique avoids having to express ones own values without the need to be explicit about why they differ – which can indeed be awkward. Another approach is to attack the science directly and again not discuss the values that animate the advocacy. But let’s be clear, neither of these approaches are good faith arguments – they are merely tactical.

People and scientists who value rationality should reject them.

References

U. Büntgen, “The importance of distinguishing climate science from climate activism”, npj Climate Action, vol. 3, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00126-0

C.W. van Eck, L. Messling, and K. Hayhoe, “Challenging the neutrality myth in climate science and activism”, npj Climate Action, vol. 3, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00171-9