2023 appears to follow an upward trend in the North Atlantic/Caribbean named tropical cyclone count

1 min read

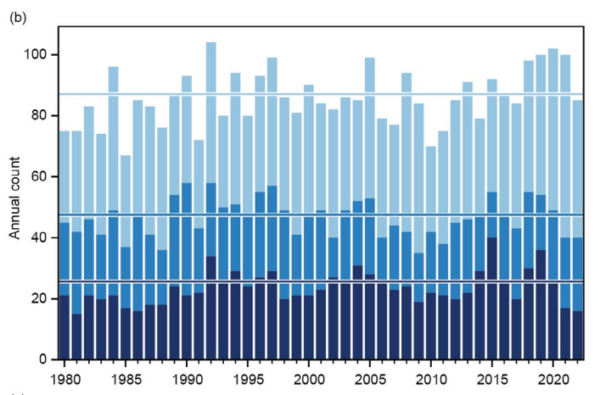

This year’s (2023) tropical cyclone season in the North Atlantic and Caribbean witnessed a relatively high number of named tropical cyclones: 20. In spite of the current El Niño, which tends to give lower numbers. But it appears to follow a historical trend for named tropical cyclones with an increasing number over time.

The curve presented above is an update of the analysis presented in 2020 and posted here on RealClimate.

The relative high number of tropical cyclones in 2023 seems to contrast the most recent assessment report from the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC), which concludes that the number of tropical cyclones is likely to decrease or remain unchanged with global warming:

The proportion of tropical cyclones that are intense is expected to increase (high confidence), but the total global number of tropical cyclones is expected to decrease or remain unchanged (medium confidence).

(IPCC assessment report 6 – technical summary TS.2.3, p. 70)

Moreover, the recent 5th National (US) Climate Assessment, NCA5, concludes in a similar vein that

[HighResMIP with resolutions between 20 and 50 km from CMIP6] simulations support the conclusion of a global decrease in tropical cyclone frequency together with an increase in intensity with warming.

These conclusions are mainly based on global climate model simulations, but current state-of-the-art global climate models are not really designed to capture all processes playing a role in such storms (e.g. convective processes and cloud microphysics).

A relevant question, therefore, is whether the evaluation of simulated historical tropical cyclones records demonstrates sufficient skill.

The observed tropical cyclone record

On a global scale, the number of tropical cyclones appears to be fairly constant as shown in the figure below, a reproduction from Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) State of the Climate 2022:

In other words, the statistics presented in BAMS State of the Climate seems to be more in line with unchanging numbers rather than a decrease.

It’s an interesting situation if there are different trends for all tropical cyclones on the one hand and the most intense ones on the other, or if there are trends that point in different directions over different ocean basins.

Such differences need an explanation because they would be caused by different physical conditions, processes or mechanisms.

Intense versus total number of tropical cyclones.

All cyclones, including the most intense ones, start as weak disturbances which intensify over time. A decrease in the total number of tropical cyclones, but more of those with greatest intensity, may imply that the threshold for cyclogenesis taking place is raised, reducing “infant tropical cyclones”, with a simultaneous adding of “fuel” so that they grow faster.

For instance, less frequent easterly waves off the African continent needed for triggering, or increased wind shear tearing them apart, may keep the number of new cyclones developing low.

Warmer sea surface, on the other hand, may boost their growth once they have been formed.

But recent hurricane seasons indicate both more tropical cyclones as well as more intense ones, at least over the North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea.

We have discussed the statistics on tropical cyclones in previous posts here on RealClimate: ‘Climate Change and Tropical Cyclones (Yet Again)’ (2008) and ‘Does global warming make tropical cyclones stronger?’ (2018).

Support for the warm-area-connection?

The said assessment reports seem to have ignored empirical studies on tropical cyclones statistics, such as indications of more tropical cyclones with greater ocean surface area with sufficiently warm water to sustain tropical cyclones (Benestad, 2009).

It seems that area-based climate indicators have traditionally not been widely appreciated in the climate research community (link).

A recent paper may provide support to the notion of the surface area of warm ocean playing a role for the total number of tropical cyclones. Shan et al. (2023) observed a significant seasonal advance of intense tropical cyclones since the 1980s in most tropical oceans. They found rates of earlier occurrences 3.7 and 3.2 days per decade for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, respectively, associated with earlier onset of favourable oceanic conditions.

The widening of the time window for the season is analogous to a spatial extension of warm sea surface area. The connection between the number and warm oceans can be found both in temporal and spatial dimension.

The quality of tropical cyclone observation

One question is whether the observed record gives a representative picture of the past and if there were many tropical cyclones in the past that were not caught by observers.

Tropical cyclones are not subtle phenomena. They create huge waves and swells. After all, surfers often enjoy their legacy.

An increase in the number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean points to increased risks for Florida which is highly exposed to tropical cyclones and sea level rise.

References

R.E. Benestad, “On tropical cyclone frequency and the warm pool area”, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 635-645, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-635-2009

J. Blunden, T. Boyer, and E. Bartow-Gillies, “State of the Climate in 2022”, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, vol. 104, pp. S1-S516, 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/2023BAMSStateoftheClimate.1

K. Shan, Y. Lin, P. Chu, X. Yu, and F. Song, “Seasonal advance of intense tropical cyclones in a warming climate”, Nature, vol. 623, pp. 83-89, 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06544-0